I grew up thinking that Canada was the antithesis of the United States in its treatment

of minority groups. In my mind, this was especially true of African Americans;

the US had cotton plantations, while we

had the Underground Railroad. Black History Month inspired me to do a bit of

reading, and I’ve discovered that sometimes the true story is not so tidy. Let’s

look back 230 years to the founding of Canada’s first black community –

Birchtown, Nova Scotia.

Birchtown

has its roots in the Loyalist migration out of the American colonies during the

Revolutionary War. Those who refused to take up arms against the British, or at

least doubted that the British were trying to enslave them, were ostracized by their

communities. Strangely, the movement towards liberty and freedom had led to vicious

persecution against all dissenting voices. Just over a decade later, the French

Revolution would do much the same.

Those

among the 70,000 who remained loyal to Britain came from all levels of society.

They were soldiers, labourers, farmers, artisans, merchants. They were Dutch,

English, colony-born, and German; Quakers, Methodists, and Huguenots. And among

their number were 3,000 African Americans.

During

the Revolutionary War, British authorities had encouraged slaves to leave their

American masters, and they were promised freedom if they fought for the crown.

Many took up the offer, and after the war was over, migrated north to find

refuge in the remaining British colonies. Most of their number gathered

together to settle in Shelburne, Nova Scotia. True to their word, the

authorities had granted them land – albeit, smaller plots in less desirable areas

– and there they settled on the other side of the Shelburne harbour. They named

their community Birchtown in honour

of the British commander who had authorized their passage from New York.

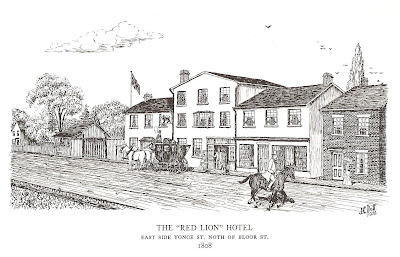

.jpg) |

| A black woodcutter in Shelburne, Nova Scotia - 1788 |

Like

us, they wanted to live free of prejudice, to own property, to give a promising

future to their children. They arrived in Nova Scotia dreaming of a “promised

land” – and, appropriately, one of their prominent leaders was named Moses. This

Moses Wilkinson was a former slave and fiery Methodist preacher. Moses helped

to lead spiritual revival in Birchtown, and his presence led several young men

to take up the ministry as well. And his labours did not pass unnoticed. So

many of their number belonged to the Methodist denomination that John Wesley,

the founder of Methodism, learned of the community and wrote to encourage white

Methodists in Shelburne:

The

work of God among the blacks in your neighbourhood is a wonderful instance of

the power of God; and the little town they have built is, I suppose, the only

town of negroes that has been built in America – nay perhaps in and part of the

world, except only in Africa… Give them all the assistance you can in every

possible way.

Sadly,

Wesley’s views were not shared by many of the white settlers in the area. Residents

of Birchtown faced oppression, and even violence at the hands of their neighbours.

They weren’t used to the Canadian winter, and their poor farmland was scarcely

able to produce a crop. To sustain themselves, they were often forced to work

in the lowest jobs for insulting wages. Perhaps the strongest testimony to their

conditions was that, when the opportunity came for free passage to Sierra Leone

(the new British colony), more than one third of Birchtown took up the offer.

I’ve

come away from this story thinking that we Canadians have a small share of

moral high ground on this topic. I am

proud of the Underground Railroad, but we must grant that there is more to the

story than that.

Sources

History of the Canadian

Peoples, by

Margaret Conrad and Alvin Finkel

The Structure of Canadian

History, by

J.L. Finlay and D.N. Sprague

Black

Loyalists: Our History, Our People http://blackloyalist.com/canadiandigitalcollection/index.htm

.jpg)